When a daughter was conceived in Ancient Greece, the patriarch became responsible for arranging her marriage with a provision for a dowry, a financial package for the groom’s father whilst he selected a suitable husband and son in law for his family. When his daughter had turned fourteen, his search would begin whilst typically, the men would be approaching their mid to late twenties and early thirties as a wife was chosen for them.

Deemed appropriate for men to marry late was their desire to complete military obligations before starting a family. It was a family expectation and included the ‘Sowing of the wild oats’ before a man settled down to raise a family. However, it was not considered a desire to prolong the joys of the single life for a young woman and with a great shortage of females at the time, due to the unwillingness of fathers to raise girls who had to be supplied with dowries, the prayers of the men were focused on male children, thus their prayers were answered.

It was also considered the right thing to do when a man was on his death bed to bequeath his property to his sons now that he had no further need for it, but his emotions were in a quandary when he was expected to hand over a large sum of money to his daughter’s father in law while he was still expected to support himself and his own wife.

Once a suitable husband was sought however, a meeting was then arranged succeeding his choice and together, the fathers of the intended couple would be conducted with only their best interests foremost in discussion whilst those of their progeny would be the least of their consideration.

A proaulia was arranged and the young bride was to spend her last few days with all of her female relatives. It was a time to prepare for the wedding and the proaulia was a feast during which the newly betrothed made offerings to the gods, Artemis and Aphrodite.

At a preordained wedding, strict rituals were followed. The ‘ceremony’ would commence with a bathing ritual in sacred water during which time her father would cut off his daughter’s hair. It was a significant rite of passage before marriage. Cutting the hair was dedication, an offering that symbolized the bride’s separation from her childhood and her initiation into adulthood.

Gifts of toys were offered, establishing a bond between both bride and the gods who would protect her during her transition. Later in the morning, the groom and his friend would travel in a chariot drawn by mules or horses depending on the purse of his own father, to the father of the bride’s home where he would share a breakfast feast.

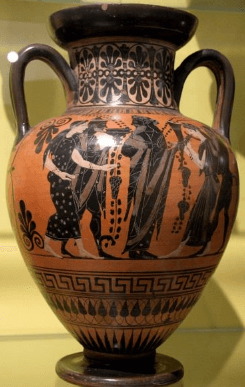

The gamos, a marriage ceremony, began with a sacrifice, as the future wife cut off more of her hair to symbolize her virginity. The two people would then bathe in a loutra, a ceremonial bath of holy water, after which the water would be poured from a loutrophoros. A smaller vessel for later use.

The gamos, a marriage ceremony, began with a sacrifice, as the future wife cut off more of her hair to symbolize her virginity. The two people would then bathe in a loutra, a ceremonial bath of holy water, after which the water would be poured from a loutrophoros. A smaller vessel for later use.

The Athenian marriage became a series of events that over time appeared as a betrothal in front of witnesses during which the transfer of the dowry to the groom was documented in stone. No record was ever kept, therefore the witness’ testimony was vital as proof.

After the men had eaten at the feast of the bride’s home, the bride and her female family, relatives and friends would join the feast and there they would gather to celebrate the union of new husband and wife. When the sun was on the horizon, the music was enjoyed and much dancing was joined with celebration until fruit and nuts, the symbols of fertility, prosperity and health were thrown over the bridal couple. After much celebration, the young bride was taken back to her groom’s parents where she was welcomed at the fire’s hearth, the heart of the young greek man’s childhood home and again, the young couple was showered with fruit and nuts.

After much celebration, the young bride was taken back to her groom’s parents where she was welcomed at the fire’s hearth, the heart of the young greek man’s childhood home and again, the young couple was showered with fruit and nuts.

Consummation of the wedding would produce a child from the union for the young bride to be accepted into the groom’s family. In the event, she was baron, and could not conceive a child, the husband had the right to divorce her and upon that act, the remaining dowry was returned to the bride’s parents.

Divorce on the grounds of adultery was granted and again, the remains of any dowry returned to her family in cash. However, during marriage; nor the groom or his family discussed anything in relation to his union in case it brought unwanted attention from unrelated males of the area.

Whilst children were born to an arranged union, it often took many years for ‘Love’ to be felt as a genuine emotion between the two people. But when having raised several children and a grandchild was produced, there was a reckoning, an acceptance and in many cases, love grew throughout old age.

The dowry provided security in the event that her husband met death or even divorced her. It meant she had an opportunity to remarry if she was young enough and could still bear children. Her security was based on that purse and became the incentive for a roof over her head should anything happen unexpectedly. Curiously, it became her staff, her power over her circumstances that without it, she might not have had.

In ancient Athens, both the man and the woman could initiate a divorce. For him, the husband had the power to send his wife back to her childhood home, where her father would accept her with dowry. For the wife to obtain a divorce, she had to appear before the archon. The divorce could only be initiated by the father of the bride if she had not been able to present her husband with a child.

If she was found to have committed adultery, her husband was obliged to divorce her and did so under the threat of disenfranchisement. It appears barrenness was to blame for many a divorce.

History suggests that Plato made moves to abolish the dowry in hopes of making a woman less arrogant and men less servile. With what she had, a woman had the power to leave the union which of course, caused financial heartache for her husband who was expected to raise the cash to send her home. In any event, he had no choice than to sell off his own assets to make enough money for her to return to her family who had a vested interest in the relationship.

In ancient times, it is assumed that although she didn’t know it, the young bride had more than the upper hand.